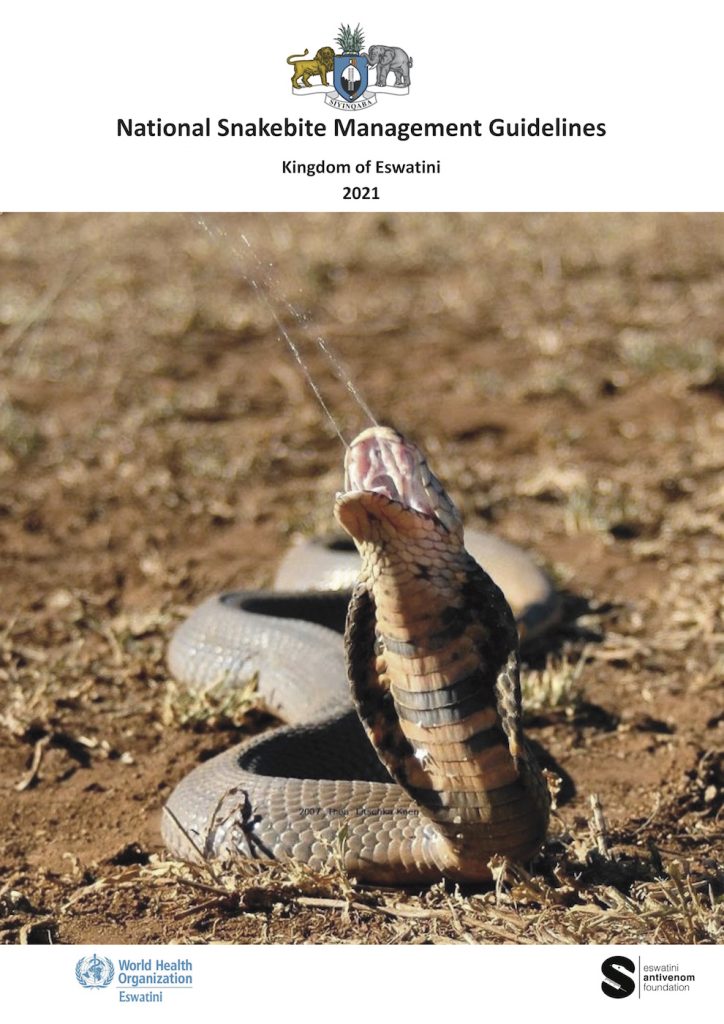

Venomous snakes in southern Africa can, in broad terms, be divided into 3 groups: cytotoxic, neurotoxic and those that can induce haemostatic toxic effects. However, significant overlap of these effects may occur. Some snake species may, for example, display both cytotoxicity and neurotoxicity. The identification of the snake responsible for the bite is usually difficult, unless a dead snake is brought into hospital with its victim and can be reliably identified. Descriptions of the snake and the circumstances of the bite may suggest a species diagnosis, but this is not often a satisfactory basis for specific treatment.

This document will serve an important tool towards ensuring that our population has access to quality snakebite treatment and care, and thus allowing the Ministry to achieve the objectives of the National Health Sector Strategic Plan 2020-2023 and National Development Strategy 2022. The guidelines will be vital in guiding clinicians in effectively discharging their duties of care and treatment to patients bitten by snakes at all levels of the healthcare system.

Most southern African scorpions are relatively harmless to humans, and although they can inflict quite a painful sting, no other toxic effects are expected to develop. However, a small number of scorpion species can cause life-threatening systemic envenoming. Children are especially vulnerable, with a mortality rate of close to 20%. Most deaths are attributable to one species, namely Parabuthus granulatus. In order for medical personnel to provide optimal patient management after a scorpion sting, they should be familiar with the clinical picture and management.

Forty-two cases of serious scorpion envenomation, of which 4 had a fatal outcome, are presented. The clinical profile, differential diagnosis and management of scorpionism are discussed. Most envenomations occurred in the summer months, peaking in January and February. An immediate local burning pain was the most prominent symptom. Systemic symptoms and signs developed within 4 hours of the sting in most instances, characterised by general paraesthesia, hyperaesthesia, muscle pain and cramps. Other striking features included dysphagia, dysarthria and sialorrhoea with varying degrees of loss of pharyngeal reflexes.

The medically important spiders of southern Africa can be divided into neurotoxic and cytotoxic groups. The neurotoxic spiders belong to the genus Latrodectus (button or widow spiders) and the cytotoxic spiders are represented chiefly by the genera Cheiracanthium (sac spiders) and Loxosceles (violin or recluse spiders). The baboon spiders (family: Theraphosidae) and the wandering or rain spiders (genus Palystes) can inflict painful bites which may be susceptible to infection.

Cases of black widow (Latrodectus indistinctus) and brown widow (L. geometricus) spider bites referred to the Tygerberg Pharmacology and' Toxicology Consultation Centre from the summer of 1987/88 to the summer of 1991/92 were entered into this series. Of a total of 45 patients, 30 had been bitten by black and 15 by brown widow spiders.

In South Africa, the medically most important cytotoxic spiders include the sac spiders (Cheiracanthium spp.) and violin spiders (Loxosceles spp). Spiders from these two genera produce cytotoxic venom, which damages the tissue surrounding the bite site causing necrotic lesions. The clinical syndrome associated with these bites is known as necrotic arachnidism. Sac and violin spiders are nocturnal and patients are usually unaware of being bitten at the time of the incident. Species like C. furculatum and L. parramae are found in and around houses where they come in contact with humans and are the most likely culprits.

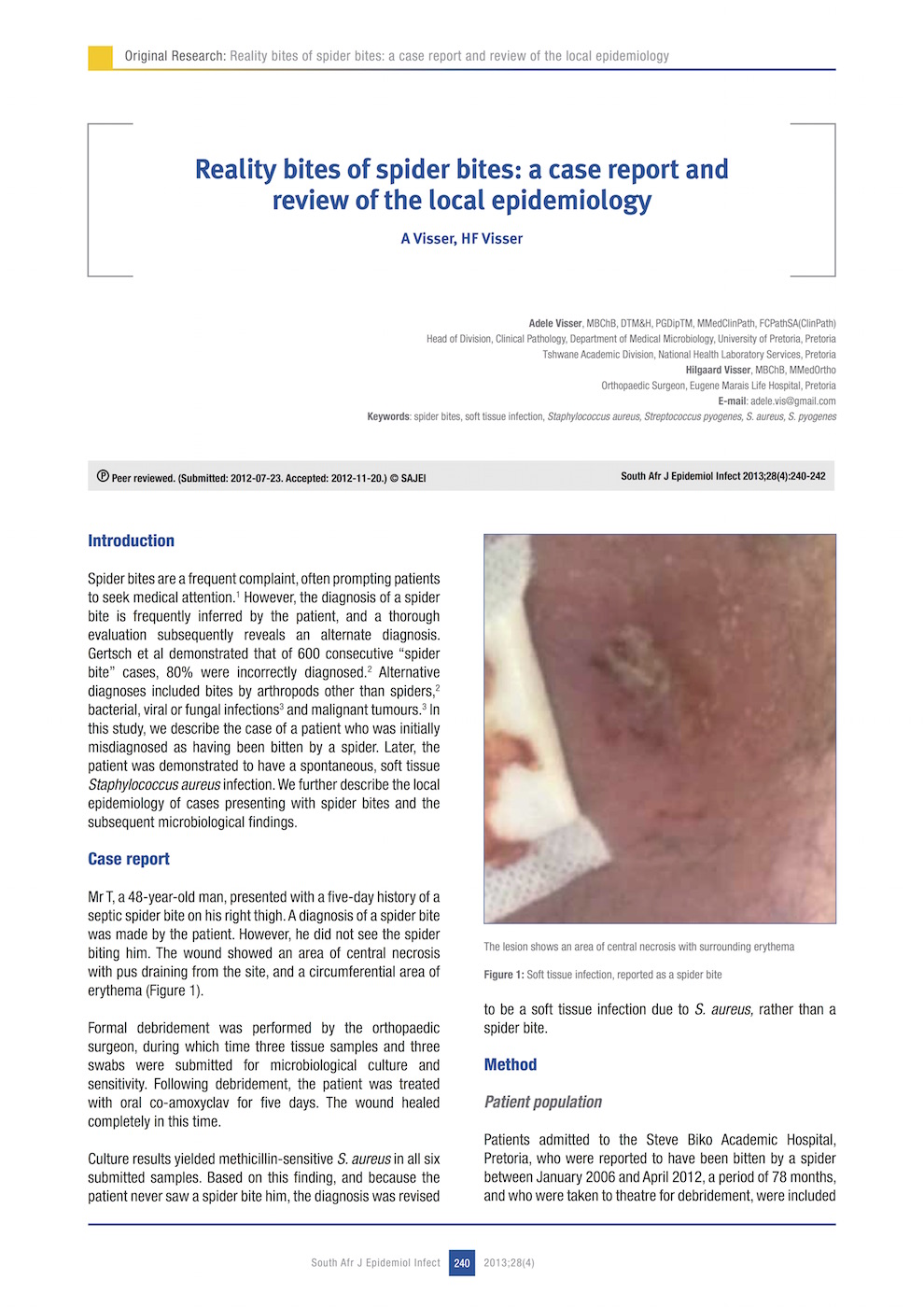

Spider bites are a frequent complaint, often prompting patients to seek medical attention.1 However, the diagnosis of a spider bite is frequently inferred by the patient, and a thorough evaluation subsequently reveals an alternate diagnosis. Gertsch et al demonstrated that of 600 consecutive “spider bite” cases, 80% were incorrectly diagnosed. Alternative diagnoses included bites by arthropods other than spiders, bacterial, viral or fungal infections and malignant tumours.

There are limited reports of definite bites by centipedes with expert identification, which are required for attribution of particular clinical effects to different species. Objective: To describe the clinical effects of centipede bites in Australia. Methods: Prospective study of calls regarding centipede exposures to a state poison information centre, from December 2000 to March 2002. Information collected included demographics, details of the exposure, local effects, systemic effects, and treatment. Collected centipedes were identified by an expert. All subjects were followed until clinical effects had resolved. Results: Of 48 centipede exposures, 3 were centipede ingestions with no adverse effects and one was a contact reaction to the centipede that resulted in erythema and delayed itchiness.

I'm on a mission to reduce the burden of spider bites and scorpion stings across Southern Africa!

Newsletter | Public Events | Books & Workbooks | Presentations | Activities |Professional Development | Shop